“Because how long do you want to go on courting a mukhabarat[intelligence] officer,” asked Uğur. “I think that the moment where he opened up about his brother, and that he committed revenge, that’s as close as you can get in this particular context.”

April 28, 2022

After a rookie militiaman secretly watched a video of 41 people being brutally killed, he knew he had to get the horrific images to the outside world

Warning: this report contains images readers may find upsetting

on a spring morning three years ago, a new recruit to a loyalist Syrian militia was handed a laptop belonging to one of Bashar al-Assad’s most feared security wings. He opened the screen and curiously clicked on a video file, a brave move given the consequences if anyone had caught him prying.

The footage was unsteady at first, before it closed in on a freshly dug pit in the ground between the bullet-pocked shells of two buildings. An intelligence officer he knew was knelt near the hole’s edge in military fatigues and a fishing hat, brandishing an assault rifle and barking orders.

The rookie militiaman froze in horror as the scene unfolded: a blindfolded man was led by the elbow and told to run towards the giant hole that he did not know lay in front of him. Nor did he anticipate the thud of bullets into his flailing body as he tumbled on to a pile of dead men beneath him. One by one, more unsuspecting detainees followed; some were told they were running from a nearby sniper, others were mocked and abused in their last moments of life. Many seemed to believe their killers were somehow leading them to safety.

When the killing was done, at least 41 men lay dead in the mass grave in the Damascus suburb of Tadamon, a battlefront at the time in the conflict between the Syrian leader and insurrectionists lined up against him. Alongside piled heaps of dirt that would soon be used to finish the job, the killers poured fuel on the remains and ignited them, laughing as they literally covered up a war crime just several miles from Syria’s seat of power. The video was date-stamped 16 April 2013.

A paralysing nausea took hold of the recruit, who instantly decided the footage needed to be seen elsewhere. That decision has led him, three years later, on a perilous journey from one of the darkest moments of Syria’s recent history to the relative safety of Europe. It has also united him with a pair of academics who have spent years trying to get him – the prime source in an extraordinary investigation – to safety while identifying the man who directed the massacre and persuading him to admit his role.

-

Warning: contains graphic images

It is the story of a war crime, captured in real time, by one of the Syrian regime’s most notorious enforcers, branch 227 of the country’s military intelligence service that also details the painstaking efforts to turn the tables on its perpetrators – including how two researchers in Amsterdam duped one of the most infamous security officers in Syria through an online alter ego and seduced him into spilling the sinister secrets of Assad’s war.

Their work has cast an unprecedented light on crimes previously believed to have been widely committed by the regime at the height of the Syrian war but always denied or blamed on rebel groups and jihadists.

Nine years later, as war rages in Ukraine, a playbook of state terror on civilian populations rehearsed in Syria is being redeployed by Russian forces, as Vladimir Putin’s so-called special military operation turns into a brutal occupation of parts of the east of the country. Military intelligence units there have been at the forefront of savagery, instilling fear into communities through mass detentions and killings of the type that characterised Assad’s brutal attempts to claw back power.

Trained by Soviet and Stasi officers in the 1960s, Syria’s security agencies learned well the art of intimidation. Often, the allegiance of those snatched at checkpoints was of little consequence; fear was the regime’s most lethal means to cling to power and it used every means available to instil it. In this case, the victims were not insurrectionists but civilians who were unaligned to either side and had accepted Assad’s protection. Their murders were widely seen in Tadamon as a message to the whole suburb: “Don’t even consider opposing us.”

In leaking the video, first to an opposition activist in France, and then to the researchers, Annsar Shahhoud and Prof Uğur Ümit Üngör, from the University of Amsterdam’s Holocaust and Genocide Center, the source had to overcome the fear of being caught and probably killed and the distress of potentially being cast out from his family – prominent members of Assad’s Alawite sect, which holds the main levers of power in what remains of Syria.

He would eventually learn that even as hundreds of people around the world worked to bring Assad to justice for war crimes, the video would end up being a standout piece of evidence in the case against the Syrian leader.

But first, Annsar and Uğur needed to find the man in the fishing hat, and they turned to the only thing they believed could help: an alter ego.

’Anna Sh’

Annsar had been a vocal critic of Assad since the outbreak of the Syrian war. Her family were members of a community that had largely retained good relations with Assad, but the conflict and the ensuing economic collapse strained alliances and Annsar increasingly found herself determined to hold Assad to account, no matter the personal price.

She moved to Beirut in 2013 and then to Amsterdam two years later, where she met Uğur in 2016. Both shared a drive to chronicle what they believed to be a genocide being committed in Syria. Piecing together the stories of survivors and their families was one way to do it. Speaking to the perpetrators themselves was another. Breaking the omertà code of the regime, however, was a task thought nearly impossible. But Annsar had a plan: she decided to turn to the internet, and find her way into the inner sanctum of the regime’s security officials by pretending to be a fangirl who had fully embraced their cause.

“The problem was that the Assad regime is very difficult to study. You don’t just walk into Damascus, waving your arms, saying well, ‘Hey, I’m a sociologist from Amsterdam and I would like to ask some questions,’” said Uğur, in the grand dark wood drawing room of the Holocaust and Genocide Centre. “We came to the conclusion that, actually, we need a character – and that character should be a young Alawite woman.”

Annsar established that Syria’s spies and military officers tended to use Facebook, and despite their secretive work lives, they tended not to make their social media settings private. She decided on an alias, “Anna Sh”, and asked a photographer friend to shoot an alluring glimpse of her face. She then turned her homepage into a glowing tribute to Assad and his family and set about trying to recruit friends.

Day and night for the next two years, she scoured Facebook looking for likely suspects. When she found a taker, she told them she was a researcher studying the Syrian regime for her thesis. Eventually, she got good at it. She learned the regime mood of the time and, together with Uğur, tailored jokes and talking points that might help with an approach. Soon, Anna Sh became known among the security services as an understanding figure – and even a shoulder to cry on.

“They needed to talk to someone, they needed to share their experience,” she said. “We shared some stories with them. We listened to all the stories, not focusing only on their crimes.”

“Some of these people got attached to Anna,” Uğur continued. “And some of them started calling in the middle of the night.”

Over the next two years, Annsar lived and breathed her new persona. At times she recoiled from who she had become – someone who had got into the minds of her prey and could at times understand them on a raw human level that eclipsed the clinical boundaries of her research.

But the snap back to reality was usually sudden. Many of those she had spoken to had been active parts of a killing machine, others were willing parts of the cabal that enabled them. Her health took a toll, as did her social life and her sanity. The prize was worth it, however. If she could find the gunman in the video, she could start to bring justice to the families of those he killed. And, maybe, she could start what few others had managed in the decade-long conflict: begin a process that irrefutably linked the Syrian state to some of the war’s worst atrocities.

In March 2021, the breakthrough finally arrived. Anna Sh’s Facebook following had by then won the confidence of more than 500 of the regime’s most devoted officials. Among her trawls of their friends and photos, a distinctive moon face with a scar and facial hair stood out. He called himself Amgd Youssuf, and he looked very much like the gunman in the fishing hat that she had exhausted herself looking for. Soon afterwards, Annsar, or Anna Sh – by now it had become difficult to distinguish the two – received corroboration from a source inside Tadamon that the killer was a major in branch 227 of the Syrian military intelligence service.

“The relief was indescribable,” she said. “Here was someone who held the key to it all. And now I needed to make him talk.”

Annsar remembers well the moment she hit send on her friend request, and the excitement she felt when her prey accepted. After all this time, the bait had been set. Now she needed to reel him in. The first call was fleeting; Amjad was suspicious and ended the call quickly. But something in that initial conversation had whetted his curiosity. The hunter had become the hunted. Was it the thrill of talking to a strange woman, the need to interrogate someone who dared to approach him, or something else? Either way, when Amjad video-called three months later, Annsar pressed record, and “Anna” answered the call.

After all these years, there he was; stern at first, very much in character as a spy who controlled all his conversations and readily deployed stony silence as a weapon. He uttered few words, and when he did speak he mumbled, forcing his listener to strain to hear him. Anna Sh did all she could to disarm Amjad, grinning sheepishly, giggling and deferring to him as he peppered her with questions, all delivered on his terms. Gradually his frozen face begins to relax, and Anna won the floor. She asked him about Tadamon.

And then she asked a question that changed the tone of the whole conversation: “What it was like to go hungry, not to sleep, to fight, to kill – to fear for your parents, for your people. It’s a huge responsibility – you carried a lot on your shoulders.”

Amjad sat back in his chair, as if to acknowledge that somebody had finally understood his burden. From then on, he was in the interrogation seat. The conversation was no longer his. Anna had an answer for every one of his replies; building him up, putting him at ease and puffing his ego. Much like Jennifer Melfi was to Tony Soprano, she had become to him a therapist, a sounding board, a trusted woman that could get to know his mind without, it would seem, passing judgment.

“I don’t deny that I was excited talking to him,” said Annsar. “So I was smiling. Because wow, you’re talking to him. But to know their stories, we need to convince them that we are just researchers. So they open up. It’s not a result of one interview – it’s a result of four years undercover. Gradually, I learned to dissociate myself. I created this girl who is really admiring their deeds. It’s tough. After you close the laptop, you feel like it’s heavy stuff, but it’s needed. And I wanted to see him as a human.”

Throughout the summer of last year, Annsar and her alter ego, with Uğur often sitting just off screen, tried to persuade Amjad to talk. Getting inside the head of a killer was one thing, but gathering real information about why he did and extracting admissions was another. They trawled his Facebook profile for clues, and came across a photo of a younger brother, and poems Amjad had written after his death in early 2013, three months before the Tadamon massacre. Anna kept pestering him for another call, but he remained elusive. Then late one night in June, her Facebook messenger lit up. It was Amjad. Here was her chance to nail him down.

‘I killed a lot’

Amjad was more relaxed this time, dressed in a singlet with perhaps a drink or two on board. The floor was now his, or so he thought, and he began with small talk, trying to feel Anna out. She seized her moment and asked about his brother, and the feared killer and enforcer started to weep. Anna switched to Melfi mode as he told her he had to stay in the military despite the risk of his mother being forced to grieve another son. “You did what you needed to do,” he said.

And then came Amjad’s first real admission. “I killed a lot,” he said. “I took revenge.”

As if to recognise the gravity of the moment, Amjad shut down the conversation and ended the call. Over the next few months he was difficult to find, responding only on chats and asking when Anna was returning to Syria. Who was this woman who had gotten under his skin? When would he get the chance to interrogate her on his own turf and terms?

Amjad started to play the role of the jealous boyfriend, asking who Anna was with, whether she drank and where she was.

Annsar, meanwhile, was starting to feel that her alter ego had reached the limit of her powers, and that Anna Sh needed a rest, just as she did. The character had spoken to up to 200 regime officials, some of them direct perpetrators in murders, and others part of a community that had aided and abetted Assad’s increasingly brutal attempts to cling on to power. They had started to speak among themselves about the mystery woman in all of their inboxes.

Late last year, after Annsar had spoken to a woman who accused Amjad of assaulting her, she had had enough. All this empathising with perpetrators had started to seep into her soul. So, too, was living a character.

“Annsar also deserves to live,” she said. “And then the question was, where is Annsar? Who is Annsar now? Lost in the research? Anna was able to pretend in life and as an Alawite, pretend for hours here in Amsterdam. And I think Anna went so far, it’s not only a digital identity. Where is the original person in all of this? Where is Annsar? So I decided to execute Anna.”

On a cold morning in January this year, Uğur and Annsar packed a small box with a printout of Anna’s Facebook profile, a sword used as a symbol by the Assad regime and some trinkets and drove to a nature reserve outside Amsterdam. There, they dug a hole and buried the character, with a startled dog walker the only other person to bear witness to the demise of a digital sleuth whose body of work would have made any real spy proud.

“I mean psychologists and therapists will tell you that if you have a particularly difficult period, you can mark that period with a ritual,” said Uğur. “So ritualising something actually helps you put it behind you. I thought, actually, good riddance.”

It was time for the two researchers to start focusing on the material they had collected and had not been able to process while so deeply immersed in the character they had just buried in a forest with a minute’s silence

“I laugh about her all the time,” reflected Annsar. “We always remember Anna.”

But there was one more thing they needed to do; confront Amjad with what they knew about him.

“Because how long do you want to go on courting a mukhabarat[intelligence] officer,” asked Uğur. “I think that the moment where he opened up about his brother, and that he committed revenge, that’s as close as you can get in this particular context.”

Over Facebook messenger, Anssar, using her real identity this time rather than “Anna”, sent Amjad a 14 second sequence of video.

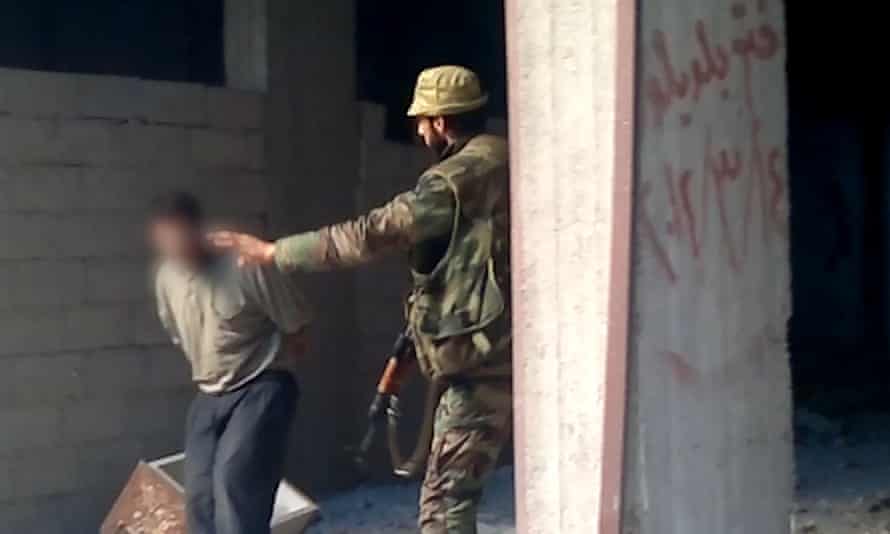

“His first question was: ‘Is that me in the video?’ I said: ‘Yes it’s you.’ He said: ‘Yeah, it’s me. But what does this video tell? Nothing. I’m arresting someone, and that’s my job.’”

Realising the consequences of what he had just been shown, Amjad then railed against members of the National Defence Front, the militia that the rookie who had leaked the video had belonged to. He described them as thugs and killers and said he was not like them.

Then the subterfuge stopped, and Amjad defiantly embraced what he had done. “I’m proud of what I did”, he wrote in a message, before threatening to kill her and her family.

Neither Annsar nor Uğur have responded to Amjad since February and have blocked him from their social media accounts. However, he has tried to reach out several times. He is clearly nervous about what lies ahead, as well he may be. War crimes prosecutions in Germany have started to break the armour of impunity that has shrouded the Assad regime in Syria. Yet those court hearings do not contain the same overwhelming evidence as depicted in the Tadamon massacre video.

Before this story could be told, however, one man needed to get to safety – the person who had leaked the video to a friend in France, and then to Uğur and Annsar. Some time in the last six months, he started his dangerous journey.

The source’s escape

Leaving the regime in Syria is never easy. Anyone hoping to travel to other parts of the county, or especially abroad, faces a long process of questioning before being allowed to do so. Although Assad retains power, the area he controls has shrunk, and two powerful overlords, Iran and Russia, have veto over many state decisions. Opposition groups retain control of the north-west, and the Kurds have aegis in the north-east. Syria remains broken and unreconciled; a place where even family members can be suspected of being traitors in waiting.

And that is how it was when a young man set off from the Syrian capital for Aleppo in the past six months on the first leg of a journey that would take him to the opposition-held north, then to Turkey and onwards to Europe.

The drive to Aleppo was a nervous one. He had been allowed to leave, but would the dreaded intelligence units catch up with him before he made it beyond their clutches? On Aleppo’s northern outskirts, a colonel from the 4th division of the Syrian army pocketed a $1,500 (£1,187) bribe in return for allowing the man across the no man’s land separating both sides. The journey was delayed a day, as a Captagon shipment was readied by the 4th division to cross the same route. Shortly after, a truck carrying dozens of kilos of the stimulant, made and distributed by the regime and exported across the Middle East, made its way to the opposition-held north.

The source soon followed. Several weeks later, Annsar met him in Turkey, where gaps in the story of Tadamon were filled in over weeks of discussions, and notes for a war crimes prosecution steadily put in order.

In February, Uğur and Annsar handed over the videos and their notes, comprising thousands of hours of interviews, to prosecutors in the Netherlands, Germany and France. In the same month in Germany, came the first ever prosecution of another Syrian military intelligence official, Anwar Raslan, for his role in overseeing the murder of at least 27 prisoners and torture of at least 4,000 others. He was convicted of crimes against humanityand has been imprisoned for life.

Annsar remains estranged from her family and in her words, is not the same person she was before she started this project. “But it was worth it,” she said. “It was exhausting, but I hope our work will help bring justice.”

Tadamon these days is a bustling part of the capital that looks like war never darkened its doorsteps. Much of the damage and the atrocities have been covered over by buildings, carparks, or piles of the flotsam and jetsam of conflict. Annsar and Uğur remain convinced that many more massacres took place there and have been piecing together locations and the names of those who went missing in the savage tussle for control of the suburb.

“The locals blame the regime,” said Uğur. “They know who killed their loved ones. The strange thing is that the people who were killed in this video were not dissidents, they were onside with the regime. You can see they are not malnourished. They are straight from checkpoints, not dungeons. They were killed as a warning not to consider crossing sides. Their families deserve justice.”

The source, meanwhile, is safe outside Syria. In fleeing his surroundings – the innermost circle of the Assad regime – he has condemned himself to a life of exile. “He is happy with his decision,” said Annsar. “Sometimes people just want to do the right thing. If I’ve learned anything out of this, it’s that there’s good in people. That truth can still eventually see the light.”