Government Demolishes Homes, Denies Property Rights

October 16, 2018

Human Rights Watch spoke to seven Syrians who had attempted to return to their homes in Darayya and Qaboun, or whose immediate relatives attempted to return in May and July. Residents said that they or their relatives were unable to access their residential or commercial properties. In Darayya, they said, the government was imposing town-wide restrictions on access, and in Qaboun they said, the government either had restricted access to their neighborhoods or had demolished their property.

The Syrian government recaptured the towns after large-scale offensives that included indiscriminate attacks on civilians, and the use of prohibited weapons. The offensives caused extensive damage and resulted in mass displacement of thousands of residents.

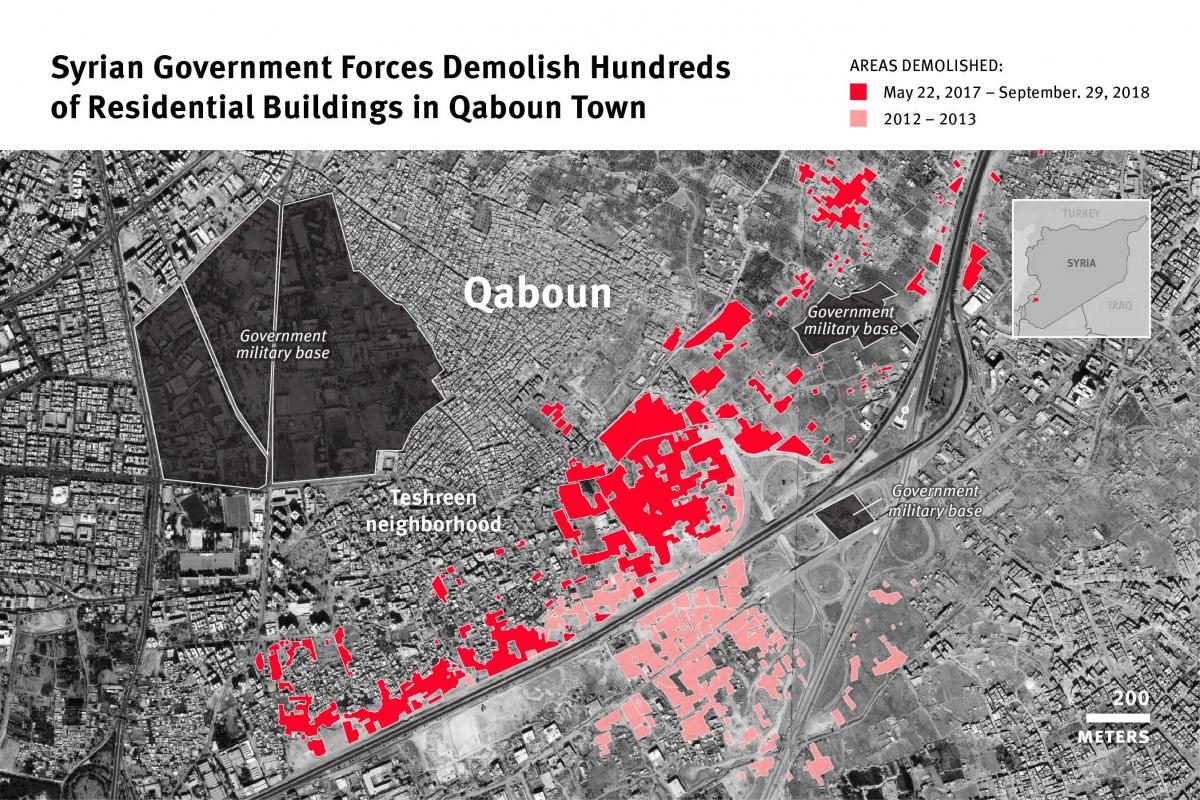

Based on media and government statements issued between May 2017 and October 2018, the Syrian government announced that it was destroying tunnels created by anti-government groups, as well as explosive remnants armed groups left behind in Qaboun. However, satellite imagery Human Rights Watch reviewed during this period showed that the government demolished houses with heavy, earth moving machinery such as bulldozers, and excavators as well as with the uncontrolled detonation of high explosives, which is inconsistent with closing underground tunnels.

Human Rights Watch also compared impact sites from the airstrikes with the demolitions. Human Rights Watch found that while many buildings were most likely damaged in airstrikes or ground fighting, but it was clear that many of the buildings demolished were also visibly intact and potentially inhabitable and were not demolished because they were damaged by airstrikes.

As one refugee put it: “They took our children, our blood and now our property – what is left for us to return to?”

Preventing displaced residents from accessing and returning to their homes without an apparently valid security reason or providing alternatives to the displaced communities makes these restrictions arbitrary, and most likely amounts to forced displacement, Human Rights Watch said.

International law guarantees freedom of movement for people who are in a country lawfully. Restrictions should only be imposed if they are provided by law, necessary to achieve legitimate aims, nondiscriminatory, and proportionate – that is, carefully balanced against the specific reason for the restriction.

In imposing restrictions on entry and exit from Qaboun and blocking return to Darayya entirely without providing a legitimate reason, or individualized security screenings of residents seeking to enter or leave, the government is violating its obligations to guarantee freedom of movement. Given the time that has passed since the recapture of these areas, and the scale of impact of these restrictions, they also appear to be disproportionate.

International humanitarian law also prohibits “wanton destruction” of property, and deliberate, indiscriminate, or disproportionate attacks against civilians and civilian objects. The scale of the demolitions, and the fact that the government had retaken the area for at least a year, indicates that these demolitions are likely disproportionate, and may be war crimes.

The restrictions on access, demolitions, and confiscation of property also affect displaced people’s ability and willingness to return to their areas of origin, Human Rights Watch said. Refugees indicated that their inability to go to their areas of origin and the lack of guarantees that security will be maintained there are reasons they would not return. Others said that this is only the latest in a series of Syrian government actions showing disregard for the civilian population.

Russia, and other countries that are calling for the return of refugees, should use their leverage with the Syrian government to ensure that the property rights of displaced people seeking to return are protected, and that the government does not expropriate or demolish their properties arbitrarily and without providing them with alternatives.

Donor countries, investors, and humanitarian agencies operating in areas retaken by the government should ensure that any funds they provide to programs aimed at rebuilding and rehabilitating structures in areas retaken by the government meet certain standards. They should make certain that their funds do not contribute to the abuse of property rights of residents or displaced people, and that the funds do not go to entities or people responsible for human rights violations and violations of international humanitarian law.

The United Nations should ensure that its agencies’ programming, including delivery of humanitarian aid, small-scale infrastructure rehabilitation projects and provision of services, does not contribute to violating the property rights of residents or displaced people and is not applied in a discriminatory manner.

“In demolishing their homes and restricting access to their property, the Syrian government is signaling that despite official rhetoric inviting Syrians ‘home,’ they do not want refugees or displaced persons back,” Fakih said. “Donors considering funding reconstruction to facilitate returns should be put on notice.”

The Government Restrictions

Local officials have not provided a reason for preventing them from returning to Darayya or Qaboun, or for the other restrictions on access, residents said. Other areas including Wadi Barada and al-Tadamon have faced similar restrictions.

On September 25, news outlets reported that a Damascus provincial committee report on the implementation Law No. 10 in al-Tadamon, a neighborhood in Damascus, found only 690 homes inhabitable – about 10 percent of all housing, according to an activist quoted in the report – and that residents would not be allowed to return to homes considered uninhabitable. Residents of al-Tadamon contended that the report was subjective and unfair. The news report did not make clear whether compensation or alternative housing would be provided to the residents.

In other areas, including Zabadani and al-Moadmiyeh, that are close to Darayya and Qaboun, residents have told Human Rights Watch that they are returning and have access to their property.

Darayya

Darayya is in the Damascus suburbs, eight kilometers from the capital. It was under the control of anti-government armed groups from 2012 until 2016. In August 2016, the government retook the area after a four-year siege, which ended with the surrender of anti-government armed groups, and the evacuation of the entire population.

The town is widely acknowledged to have been central to the Syrian uprising, and is strongly affiliated with the political opposition, having produced prominent political activists. Since 2012, the Syrian government has detained and tortured dozens in unofficial prisons, and retaliated with large-scale attacks on the town.

Human Rights Watch spoke to three residents, who had attempted to return or whose immediate relatives attempted to return in 2018. All three said that Darayya had been completely closed off to residents for two years with government checkpoints and physical barriers erected by government forces. To enter, one either had to have a relative in the Syrian military or pay a bribe and even then, residents could not stay in the town, they said.

“There is a large steel barricade, and several checkpoints,” said Samer, a former Darayya resident. “They don’t allow anyone in. Our house is 300 meters from the checkpoint.” One resident said that his neighbor paid upwards of $1 million SYP to be able to enter and check on his property.

Two residents who attempted to return said that officials they spoke with at civil registries and municipalities would not provide a reason for blocking access to Darayya.

A woman who attempted to return to her home in Darayya in May said that the Syrian government would not allow her in. She had returned fearing that the family’s property would be confiscated under Law 10, she said. When she went to the municipality office, officials did not allow her to visit her properties and provided no reason, saying “Not allowed means not allowed. We don’t question these things in Syria.”

A young woman whose father died recently also attempted to return to check on the lands and inheritance issues. She said she was not allowed to reach her property, and that due to the lack of transparency around the policies and property registration, she was unable to resolve, or even understand, what steps were needed to ensure that her father’s property in Darayya could pass on to her.

On August 27, a Facebook page of the Darayya Executive Office, an affiliate of the Syrian government, announced that people could enter Darayya on August 28. The decision permitted residents who had registered to enter from one point in the town, and only to check on their homes. They had to leave the same day and could not resettle or remain in Darayya.

“The government would turn us away at checkpoints,” one former resident said. “At first, they said it was security reasons, and we understood, but two years later and dozens of other areas were opened, why is Darayya still closed?”

In September, the Executive Office shared lists of names and announced that people on these lists could register and obtain a permission card that would allow them to enter Darayya at any time. However, the government did not allow any to stay or return to their homes, based on comments from residents on the Facebook page and the residents had to leave the same day.

Recent media reports have implied that residents have not been able to return to Darayya because of heavy damage to the buildings and no connection to basic infrastructure, including water and electricity. However, Human Rights Watch research shows that in other areas, that were re-taken by the government later than Darayya, including Zabadani and al-Moadmiyeh, residents were allowed to return, apparently without these preconditions in place.

A woman who attempted to return to Darayya in May 2018 after the local authorities designated it for redevelopment told Human Rights Watch that the municipality blocked her from visiting her properties. She said they did allow her to submit copies of her title deeds and the number of the property to demonstrate property ownership, as required by Law 10 to not be stripped of property in redevelopment zones, but that municipality officials told her ownership would only be recognized after security clearance without explaining what that would mean. “Some people will get an approval. Others won’t,” she said. “Hopefully, our name gets on the list and they let us back. We didn’t get any promises. We’re just hoping.”

Qaboun

Qaboun is in the Damascus countryside, six kilometers from the capital. It was under anti-government control until 2017, then recaptured by the government. Between 2014 and 2017, there was a ceasefire between the parties to the conflict there.

However, in March 2017, the Syrian government, supported by the Russian military, opened an offensive to retake Qaboun. Satellite imagery Human Rights Watch reviewed shows that the Syrian-Russian military alliance bombarded the Teshreen neighborhood with heavy artillery and large, air-dropped munitions between early February and mid-April 2017. This was followed by a large ground offensive along southern and eastern edges of Qaboun between mid-April and late May 2017. Satellite imagery recorded during this period shows the presence and movement of military vehicles, including Armored Personnel Carriers and tanks, but the majority of the ground fighting was concentrated further north from the demolition zone. The Syrian government retook Qaboun in May 2017.

In Qaboun, recaptured in May 2017, state officials made certain neighborhoods off limits to residents while allowing entry into other neighborhoods, one former resident said. But even in the neighborhoods that residents can enter, the government had imposed restrictions on entry and exit, requiring people who want to go to Damascus to pay 500 Syrian pounds [US$1] and imposing a same day return requirement. Those entering the neighborhoods are required to leave their identification cards at a checkpoint on their way in.

Human Rights Watch spoke to four people from Qaboun who said that access to certain neighborhoods remains restricted and that demolitions that began in 2018 are ongoing in neighborhoods along the M5 Highway.

“Leila,” whose relatives remain in Damascus and the Damascus countryside and who asked not to be identified to protect her family’s security, said that her house was still standing when her family left in May 2017 as part of the mass displacement to Idlib after anti-government forces in Qaboun surrendered. She has not been back since:

I left in the displacement of Qaboun [after the government retook the area], and within a few months, asked one of my cousins to visit the house. We left a car there, and I wanted to make sure that everything was there. They refused to allow him in and did not give a reason. I insisted that he visit, and he paid them a bribe and they allowed him in. The house had been struck during the fighting – we were still there – and was burned but it was still standing at the time.

Her cousin visited the property again in August or September 2018, and found it razed to the ground. Leila and other residents said that only government officials are allowed to operate and demolish in the area. She said that her home was not part of an informal settlement and that the damage to the house did not warrant its destruction. She said her family received no notice, compensation, or support in finding alternative housing.

The government had previously used the excuse of clearing informal settlements to demolish homes.

Another resident, “Omar,” said his property was demolished shortly after Qaboun was retaken. He said he left Qaboun in May 2017 and was provided with pictures in June by a friend inside Qaboun that showed the destruction. He said that his house was formally registered, and not part of the informal settlements. His family also received no notice, compensation, or alternative housing. “This is the government’s usual practice,” he said. “They also demolished one of our properties back in 2012, and similarly gave no warning and no money. They don’t want us to return.”

Leila and Omar also said that the government is blocking access to several other neighborhoods including al-Falujeh, al-‘Aardiyeh, Mazra’et al-Hammam, Mashrou’ al-Wan, Mou’asseset al-Kahrabeh, and Jame’ al-Hussein. In another neighborhood, where Leila owns a second home, no reason was given for restricting access: “Last Eid [June 2018] my daughters were able to visit the property and move relatively freely. This Eid [August 2018], they tried again and were told they could not access the area.”

Human Rights Watch analyzed a time series of satellite imagery and identified hundreds of mostly residential buildings in Qaboun demolished between May 22, 2017 and September 29, 2018. The demolitions were conducted with heavy, earth moving machinery such as bulldozers, and excavators and the uncontrolled detonation of high explosives. The demolitions were concentrated in the southern end of the town along the M5 highway, over 35 hectares in total area.

Between May 22 and July 2, 2017, dozens of buildings in the southern end of Qaboun along the M5 highway were demolished. There were a limited number of air strikes in this part of town, and the majority of buildings demolished during this period appeared intact and potentially inhabitable before they were demolished. Demolitions resumed between September 13 and October 22, 2017, this time further north from the M5 highway.

A third round of demolitions began sometime between March 27 and April 13, 2018, and continued until early September. In parallel, satellite images showed dozens of dump trucks taken to the area to remove debris from demolished buildings, creating large areas of bare soil along the northern side of the M5 highway.

A satellite image taken on May 11 captured a large smoke plume and debris cloud immediately after the probable detonation of multiple residential buildings with high explosives.

In 2014, Human Rights Watch documented large scale demolitions in Qaboun neighborhoods, apparently in retaliation for affiliation with the political opposition. In all the cases, the demolitions took place with little to no warning, and the government failed to provide alternative housing or any compensation, residents told Human Rights Watch.

Three residents told Human Rights Watch that their families who remained inside Syria and visited Qaboun informed them that their houses were demolished between May 2017 and March 2018. Two of the residents shared pictures of the houses with Human Rights Watch, which showed an extensive amount of rubble, and destroyed structures and said that the property was not part of informal settlements. Human Rights Watch did not interview any witnesses to the demolitions in 2017 and 2018, but residents consistently said that they believed the government was responsible for the demolitions because they were in control of the area at the time.

One resident said that the government demolished properties of his in 2012, 2013, and 2017:

We had three homes in Qaboun. We owned them. In 2012, the government demolished the first home. In 2013, the regime took over the area, and didn’t allow a single person to go in. The buildings were not damaged in airstrikes, but they demolished them anyway, razing them to the ground. Then, end of last year [2017], after they forced us out, they demolished our final home. Nothing remains.

Law 10

The law, passed by the Syrian government on April 2, 2018, empowers the government to create redevelopment zones across Syria by decree, with extensive and in some cases formidable requirements for property owners or tenants to qualify to remain or to be compensated when they are required to move for redevelopment.

Following international pressure, the Syrian Foreign Minister confirmed that “indeed, the deadline for proving ownership of a property after the announcement of a re-development zone had been amended and extended to one year.” Diplomats and lawyers told Human Rights Watch that the Syrian government is returning the law for reconsideration in parliament. However, at the time of writing, no legislative amendment to Law 10 had been passed by parliament.

Law No. 10 replaced Decree 66 of 2012, to allow for the redevelopment of areas in the Damascus countryside. Following the passage of Decree 66, Damascus Cham Holding, a public-private partnership between the Syrian government and private investors, was created. On March 27, news reportssaid that the Damascus provincial council had approved development plans for Basilia city, the second development project, Marota City, the first development project under Decree 66 was announced as far back as 2016. These two projects include parts of Darayya, Kafr Souseh and Mezzeh, towns in the Damascus countryside. In April 2018, following the passage of Law 10, SANA announced that additional parts of Darayya will also be included in redevelopment plans.

International Law

Residents’ right to a home and to adequate housing and property is protected under international law. The treaty body tasked with interpreting the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has found that this must include guarantees of legal protection from forced eviction, including (a) an opportunity for genuine consultation with those affected; (b) adequate and reasonable notice for everyone affected before the scheduled eviction date; and (g) provision of legal remedies, among others.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Arab Charter on Human Rights guarantee the right to property. The Arab Charter states that no one should “under any circumstances be arbitrarily or unlawfully divested of all or any part of their property.” In demolishing private homes and blocking residents’ access to their properties without notice, genuine consultation or providing adequate compensation, due process, or alternative housing, the Syrian government is failing to abide by the requirements, Human Rights Watch said.

Under the UN’s Pinheiro Principles, refugees and internally displaced are also protected from discriminatory housing, land, and restitution laws. These laws must be transparent and consistent. If a refugee or displaced person is unlawfully or arbitrarily denied their property, they are entitled to submit a claim for restitution from an independent and impartial body.

Imposing collective punishment by imposing arbitrary movement restrictions or unlawfully depriving people of their property also violates human rights and humanitarian law. If the Syrian government is blocking access to these areas due to some community members’ prior affiliation with the opposition, then this may constitute collective punishment.

.

.