Despite these attempts to adapt, fear can permeate every aspect of life in Idlib

July 19, 2019

By SJAC

In June, SJAC’s Documentation Team Lead crossed the border from southern Turkey into Northwest Syria in order to spend the Eid holiday with her family. The Team Lead manages SJAC’s field team and network of documentation partners, and she is well-aware of the ongoing humanitarian catastrophe in Idlib, where indiscriminate airstrikes are placing over three million civilians in harm’s way and destroying medical facilities and agricultural land. However, she had not been in Syria since 2017, and was eager to see the situation for herself and learn what aspects of life are missed in international media coverage. She was shocked by what she saw on her trip, both the conditions civilians are living in and their continued resiliency in the face of unimaginable hardships. This week SJAC will highlight the continued urgency of the situation in Idlib by sharing some of her experience, in her own words.

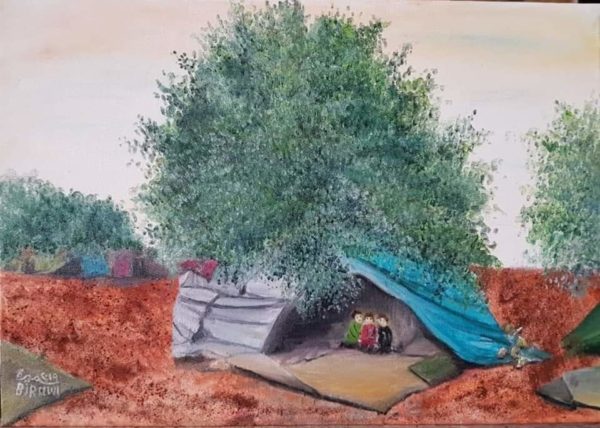

On the short road between the crossing and the city of Idlib, hundreds of families crowd under the olive trees, having received no humanitarian aid, though a few of them managed to get blankets and food from villages near the olive groves. The families wish for a tent to shelter them from the burning summer sun. . . Pregnant women are terrified to give birth under the trees, where there are no health facilities, equipment or medications. They are concerned the babies may die because of the bad conditions, including the suffocating crude oil smell emitted from generators. In the camp, I noticed many girls scratching their heads, many have been infected with lice as they haven’t taken a bath for at least ten days. Other children are infected with scabies, and the far health facilities are no longer able to receive them.

The Team Lead also observed how communities are dealing with the daily hardships of the conflict, often adapting strategies from IDPs who have survived similar conditions elsewhere in Syria.

I passed through random camps carrying in my heart the feeling of helplessness and guilt towards these people whose only sin was to want to live in dignity, but they themselves were never helpless. The men were collecting the remnants of barrels and rockets after the demining and war-destruction courses of local Syrian organizations. The women bring the water from the salty wells, fill in the empty containers, and then pour the “hudro” or sodium bicarbonate, which is used to clean the white “djellabas” for Eid, one of the most prevalent traditions in Syrian cities and villages.

The farmers accuse the Syrian government of burning their lands through airstrikes and thus destroying food security in the province. Most families have a small stock of wheat and barley and they have started to use barley and soybeans for baking, an experience that was transferred to them by the forcibly displaced families from eastern Ghouta, Madaya and Zabadani.

Despite these attempts to adapt, fear can permeate every aspect of life in Idlib.

In Idlib, the Eid games never stopped, and the market was full of people. At one of the game stalls, I stopped to buy plastic swords and Barbies for my nieces and nephews. A young girl insisted that an old man who seemed to be her grandfather buy her a barbie. The man pulled it out of her hand and walked away, without the child crying or wailing. Then the man returned and said to the salesman, “Give me that doll, I am afraid we will be killed by shelling during our return and the girl will die wishing for it”. That evening, the Syrian government bombed three “souks” (markets) in Ariha, Idlib and Kafranbel, killing a number of children.

Upon her return to Turkey, The Team Lead said, “As I left Idlib, I carried with me the voices of mothers, fathers and children who only want to stay in their houses and be safe,” and she wondered whether these voices will be heeded by the international community. Listening to her story, along with the stories of SJAC’s other documenters and the many survivors whom they interview, SJAC is once again calling on the international community to act urgently to halt attacks on Idlib and address the urgent humanitarian needs of the civilian population. The previous deal to protect Idlib was created outside the auspices of the United Nations negotiations, at Astana. It is vital that the United Nations reclaim leadership on this issue and vocally condemn the serious violations of international humanitarian law being committed by Russia and the Syrian government. In his address to the UN Security Council on June 27, Special Envoy Geir Pedersen spent more time speaking about plans for a constitutional commission than attempts to halt the violence in Idlib, and he failed to name Russia and the Syrian government as the perpetrators of the violence. Until airstrikes against civilians in Idlib halt, a ceasefire in the region should be the primary focus of the Special Envoy’s office and the international community. Meanwhile, foreign governments cannot allow concerns over Hay’at Tahrir A-Sham to interfere with the provision of humanitarian aid, and must work to increase provision of aid to civilians living under bombardment.